Composer Reuben Jelleyman: radical transformations

As a child, award-winning New Zealand composer Reuben Jelleyman had a fascination with Beethoven’s music. “I remember wondering how he put it together, what his secrets were,” he says. “I would make up stories at the piano.”

Coming from a musical family, his grandmother a violin teacher, his aunt Dorothy Ker and her husband Jeroen Speak composers, and other relatives playing instruments, Jelleyman agrees that becoming a musician was perhaps inevitable. “I tried to get out of it, but there was no hope,” he jokes. But it wasn’t till the end of high school that his route to composition became clear. “I decided to write down some music and get it played,” he remembers. “It was really exciting; the thrill of seeing it come to life was transformative.”

Jelleyman turns 30 next year, but already this quietly-spoken, modest composer has chalked up an impressive array of prizes and awards. The youngest ever finalist for the SOUNZ Contemporary Award in 2016, Jelleyman was a finalist again in 2021 and won the Award in the APRA Silver Scrolls in October this year. In between he has received multiple awards and scholarships towards overseas study, including an APRA Professional Development Award, scholarships from the Edwin Carr and Dame Malvina Major Foundations, assistance from private donors and an Arts Foundation Springboard Award in 2021.

Asked about career turning points, he immediately names the Nelson Composers’ Workshop in 2011, which he attended when in 7th form at secondary school. Ker had introduced him to New Zealand composer Samuel Holloway in Auckland, who provided composition lessons and encouraged him to attend the Workshop. “I fell into a composing community; there was a landslide of connections from the Workshop.”

Enrolled in a degree in composition at the New Zealand School of Music - Te Kōkī, Jelleyman says he “pushed the throttle to ten” but felt something was missing. “I was trying to work out what it was. I did one paper in physics and realised it was that, there was something else in my life that I’d put aside.” Does the physics inform his compositions? “Yes, it does. It’s very abstract, not really the obvious connection, but it’s a way of shaping my ideas. It’s wonderful that you can shape things using other tools, mathematical equations that create curves, symbols on paper; the mechanics had a beautiful unfurling.”

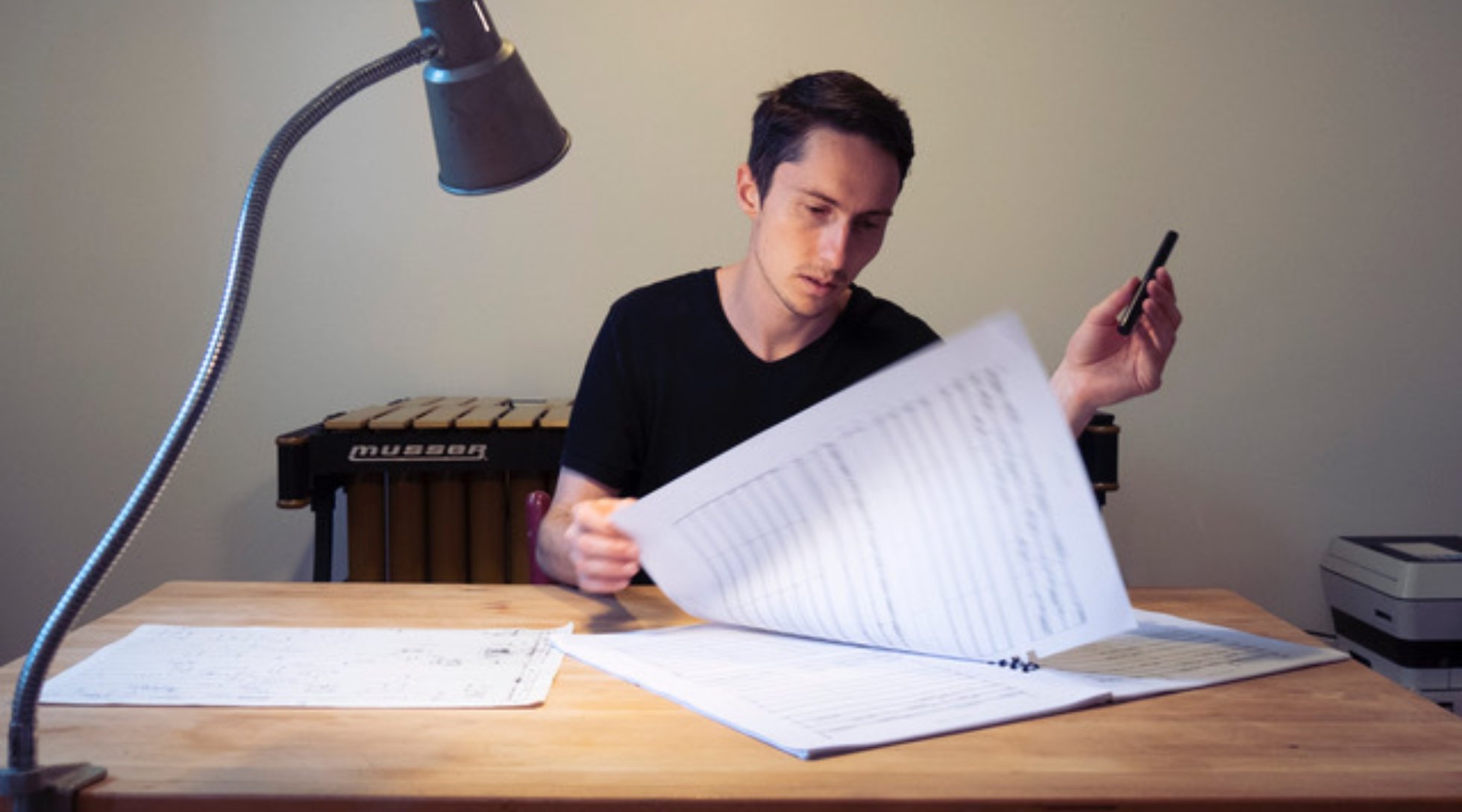

Composer Reuben Jelleyman

“…physics is a way of shaping my ideas.”

His creative work included multi-media installations, multichannel electronic works and performance as percussionist, organist and conductor. By 2016 he’d completed a Bachelor of Science in Physics and Applied Mathematics and a Bachelor of Music in Electronic and Instrumental Music. After free-lancing for a while Jelleyman headed to Europe in 2019 to study composition at the famous Paris Conservatoire.

“I wasn’t sure about further study but when I asked myself where I’d really like to go, Paris was right up there. And thinking about teachers there, Gérard Pesson was the name that came to mind.” Beginning studies at the Conservatoire, where previous alumni included Debussy, Ravel, Nadia Boulanger, Messiaen and Boulez, sounds straightforward enough, but the move included passing a formidable entrance examination.

“The exam is ruthless,” he says, “a traumatic experience!” Jelleyman took advice from former students of Pesson as he prepared. “I wanted to give it my best shot. But for New Zealanders, when we apply for big or prestigious schools, we don’t know where we sit in the queue, which was also daunting. I was very lucky to get a chance.”

The Paris Conservatoire building in the 19th Arrondissement of the city

Photo credit: Reuben Jelleyman

Having been accepted as a Masters student, and with some small scholarships available from the Conservatoire, he embarked on putting together the “patchwork” of funding required for living as a student in Paris. He had to hold his nerve. “I couldn’t find all the money at once, I just had to take steps forward, and figured that, if I had to abort at some stage, it was better than not starting at all.”

In spite of uncertainties and set-backs, including the arrival of the COVID pandemic in his first year of study in Paris, Jelleyman successfully completed his two-year degree. The stand-out experience, he says now, was “the way the Conservatoire looked after us. The professional development programme meant we had to do a couple of projects each year, where they organised everything for the performance and provided everything you’d need. The concerts were well-advertised and had a production team and so you knew that every project in your artistic portfolio for the Masters would be created in an environment where you’re supported as a growing artist, rather than just sitting in classes.”

Paris in winter

Image credit: Reuben Jelleyman

He also enjoyed the range of performances available in Paris. “I heard the professional music ensembles in the beautiful halls there, but also visiting artists I’d dreamed of seeing. Jordi Savall with his production of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo , for instance and Daniel Barenboim conducting the Staatskapelle Berlin playing Mozart and Beethoven, which was amazing! And a lot of jazz ensembles I’d always wanted to hear, like jazz guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel playing with students at the Conservatoire. Just wonderful opportunities.”

What happened in Paris when the pandemic struck? “The city was radically transformed overnight and became quiet and tranquil,” says Jelleyman. “For us composers it was a strange reprieve from all the chaos, though replaced with a lot of other chaos and a brooding uncertainty.” He was sharing a house and a “bohemian existence” with a compatible student composer flatmate but could leave home for only 30-60 minutes a day to get groceries and exercise. The lockdown in Paris was strictly enforced. “On the first day I was about to leave and then turned back to get my papers – and as I walked out the door a policeman pulled up and asked for those papers.”

For composers, he says, it was “a unique opportunity to bunk down and work on our music, which was good for a few months. Live performances got cancelled, but our projects were safeguarded, and we did recordings instead.” Some funding sources disappeared as New Zealand scholarships for overseas travel were suspended or cancelled, a “nightmare” for Jelleyman, who had to rely on emergency scholarships from the Conservatoire and on his parents.

The score of Catalogue, the work for which Reuben Jelleyman won the SOUNZ Contemporary Award in 2022

Jelleyman’s second year project in Paris, to complete his degree, was Catalogue, a big work for large ensemble, written for Multilatérale, a professional contemporary instrumental ensemble. It is the work that won him the SOUNZ Contemporary Award in October this year. Jelleyman describes Catalogue as “a chaotic collision of my musical explorations during my studies, and yet, it’s hardly the conclusion to anything. It’s more of an explosive start…”.

Beginning quietly and simply with a sustained tone that may seem to move between electronic and live sounds, it is a work that, in the composer’s words, “takes the aesthetic of electronics and recreates it in the purely instrumental ensemble.” Catalogue is sophisticated and virtuosic, incorporating moments of both expressive beauty and apparent chaos. The texture develops with eruptions of rapid, colourful instrumental flourishes, these gestures set against high pitched pulses and oscillations that sound electronic. The integration and juxtaposition of sounds and layers is skilful and thoughtful. From a moment of repose at the centre, textures and timbres change and finally the whole work returns to its starting point of a simple line, the oscillations this time a little more agitated with quiet interruptions. It’s available for listening here.

Composer Reuben Jelleyman at the APRA Silver Scroll Awards

“…winning the SOUNZ Contemporary Award was surreal”.

Image supplied

Jelleyman describes winning the 2022 SOUNZ Contemporary Award as “surreal”. He finds it very encouraging that a work written offshore, one representing a new direction for him, has been recognised in New Zealand. “It’s really nice knowing that work created by New Zealanders overseas is recognised here.”

Earlier this year Jelleyman returned to New Zealand to take up a position with Marshall Day Acoustics in Auckland. “I got really lucky,” he laughs. “It’s a great job, something different to learn, every day, about sound in every corner of the world. And our office is really musical.”

He’s carving out a little time for creative work alongside the job and he has a couple of composing projects under way. Jelleyman is enjoying the longer timeframes available and the ways his ideas can gestate more slowly than in the high pressure environment of his studies. “I’m constantly nostalgic for my life in Paris, but returning to New Zealand now has been the right step for me.”